The Intersection of Black and Green: Reflecting on Black History Month 2022

Izzie Malkani, Communications and Development Associate

imalkani@citysprouts.org

February closes on a significant symbol of hope, community and gratitude: Black History Month 2022.

Even though Black History Month is over, the education does not stop there. Black History Month is not only a time to honor the leaders and trailblazers of the Black community, but also an imperative to reflect on the current experience Black Americans live today. This year’s theme was Health & Wellness, focusing on Black pioneers’ “contributions to Western medicine, health disparities facing our communities, and… healing through education” according to the National Museum of African American History & Culture. With that, we must reflect, what is missing from society that requires us to focus on health & wellness?

The reality is that Black Americans are subjected to a multi-faceted mental and physical health crisis—and it’s linked to lack of outdoor and nature access. As our ancestors lived, breathed and fought for their natural environment, we are all inherently attuned to the natural world. Nature quite literally has ‘healing powers’; it reduces stress, it’s energizing, increases attention span, and more. Not to mention, the most impactful learning can happen outdoors where developing minds can explore for themselves the innate value of nature and the joy it brings. Unfortunately this is not possible for many Black Americans. People of color are almost 3 times more likely to live in ‘nature-deprived’ areas with poor or nonexistent access to parks, paths and green spaces. In fact, in Massachusetts, over 90% of people of color live in heavily altered neighborhoods where nature is not accessible. Compare that to less than 15% of white-dominant neighborhoods. Over the country, white neighborhoods are located in more peaceful, healthy spaces with less industrial development, less agricultural land (which can have terrible effects on human health), less oil and gas infrastructure, and fewer roads. That opportunity to “escape” should be the standard human experience, but enjoying the outdoors has become a privilege. Nature has become a luxury rather than a human right.

To make matters worse, the COVID-19 pandemic has proven that nature access is essential for maintaining our wellbeing. Not only are Black Americans less likely to take time outdoors, many in the community also have an increased risk of getting sick and dying from the disease. This is due to poor access to healthcare, working in industries where workers are exposed more to COVID-19, lack of job security, and living in crowded housing conditions. These factors are at the core of this year’s theme of health and wellness, more pertinent than ever.

How did this come to be?

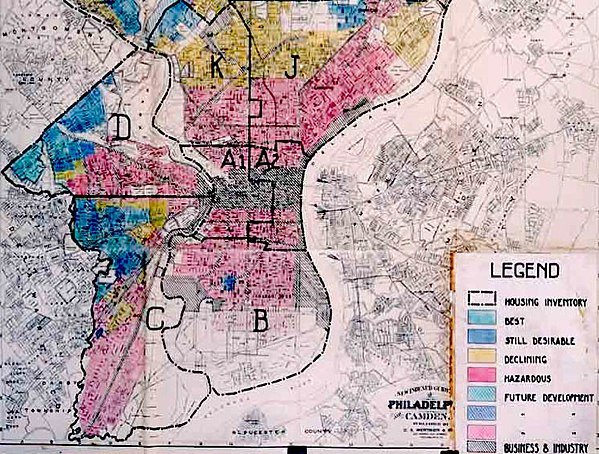

A 1936 Home Owner’s Loan Corporation "residential security" map of Philadelphia.

The US has a long history of reserving basic human rights for economically privileged (and largely white) people. A significant moment in history that impacted the community was the act of redlining in the 1930s. After the Great Depression, the federal government wanted to prevent another financial disaster by predicting which areas were and weren’t likely to succeed when given housing investments, or “mortgage security”—coding it in red or green. In other words, they equated maintaining economic stability with not investing in Black neighborhoods because they were believed to be most likely to default on their loans. Even though the practice began almost 100 years ago, inequitable housing persists and will continue to persist under our current system. Visit this website to see how your neighborhood would have been coded and for more information on redlining.

How else does lack of outdoor access affect the Black community?

Carolyn Finney

A major barrier that prevents more Black Americans from spending time in nature is that they don’t see themselves represented in that space. Author Carolyn Finney (watch her Ted Talk) believes that in tandem with her personal experience growing up in nature, Black people have been left out of the narrative and mainstream conversation of who belongs in this space. Our understanding of conservation and wilderness stems from the white, christian men that founded the movement in the 20th century like John Muir and Henry Thoreau. Being left out of the narrative comes with factual lack of representation as well as the feeling of exclusion from those represented:

Firstly, Black people have always been out in nature, just ways that don’t fit the traditional narrative. It’s common to have outdoor barbecues, go fishing and play sports–but that’s not at the forefront of how we culturally understand nature. Enjoying the outdoors doesn’t have to look the same.

Secondly, minority representation in environmental and governmental organizations is lackluster. According to a report by Green 2.0 in 2018, at the 40 largest environmental organizations in the US (think the Sierra Club, Defenders of Wildlife, Greenpeace), 80% of the staff are white. In the top 10 biggest environmental groups, or Big Green Groups, 22% of the senior staff are people of color in a country that is about 40% people of color. How can minorities be interested in such groups and causes where they’re clearly not represented?

The communities that are most affected have the least power in making decisions that can change their lives. Not to mention, Black Americans are causing significantly less damage than their white counterparts, but facing the consequences significantly more.

This is why POC role models are so important. It’s so hard to break out of the mold and be the change you want to see–but it has been done!

George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver

Carver was a brilliant, extremely influential scientist from the 19-20th century. He represents Black American innovation in nature, but his story is left out of the traditional narrative. Carver started out as a boy with a future unbeknownst to him, born 1 year before slavery was outlawed. After being separated from his family, he was adopted by a white couple who taught him how to read and write. He had the rare opportunity to apply his knowledge to the natural world around him, becoming interested in agriculture at a young age which carried into his adult life. Carver became the first African American with a Bachelors of Science degree, and later earned his Master’s degree in Agricultural Sciences. Despite the numerous systematic challenges against him (simply finding a prestigious university that would admit Black people), he tried to find every opportunity to enrich his education. His work with identifying and treating plant diseases was so remarkable, that Booker T Washington (one of the most prominent Black Americans at the time) wanted Carver to run the agricultural school at Tuskegee University, to which they signed the contract with the condition that the university were to keep its all-black faculty.

The most notable invention of Carver’s is his way of crop rotation. He found the optimal method of combining soil-depleting plants with nitrogen-fixing plants to make sure the soil could sustain large yields of crops. Over the monocropped cotton fields that were stripped of nutrients, he grew peanuts, soybeans and sweet potatoes which helped agricultural industrialization to take off. Unexpectedly, there ended up being a surplus of peanuts to which Carver invented new ways of using them in ways never imagined before, nutritionally and medinically. He is the reason why we consume peanuts so prolifically!

Franklin Roosevelt posthumously awarded him a monument that had only been given to US presidents. But his story hasn’t been told enough. We need more education about figures like him, showing Black children their potential to make strides in STEM. And the more we increase representation of Black people outdoors, folks can feel safer and less singled out in these spaces. We also must decodify whose activities belong to whom: as certain activities like camping and hiking are commonly associated with white people, it prevents participation in making nature a space for everyone. In order to change perception of these ideas, we must have empowered local communities and bottom-up initiatives that let them empower themselves. Ultimately, change comes down to educating our younger generations differently, in a way where more children feel free to challenge the status quo and make a brighter future for themselves.